For the journalism students in Andrew DeVigal’s “Engaged Journalism” course at the University of Oregon, the assignment is anything but academic. Their classroom is the small, rural communities of Oregon, and their challenge is profound: How can journalism do more than just report on a community? How can it be more responsive to its needs? How can it help a community thrive? Particularly, they are exploring how local journalism can contribute to a broader civic infrastructure that fosters community connection, democratic participation, and resilience.

A Community-Centered Path to Change for North Carolina

The North Carolina Local News Lab fund has been using the Civic Information Index since the summer of 2024 to ground their grant-making in data and reinforce a holistic, community-centered approach to supporting news and information needs in the state. We sat down with the fund’s director, Lizzy Hazeltine, to understand what this means in practice.

Challenging assumptions, mapping opportunity

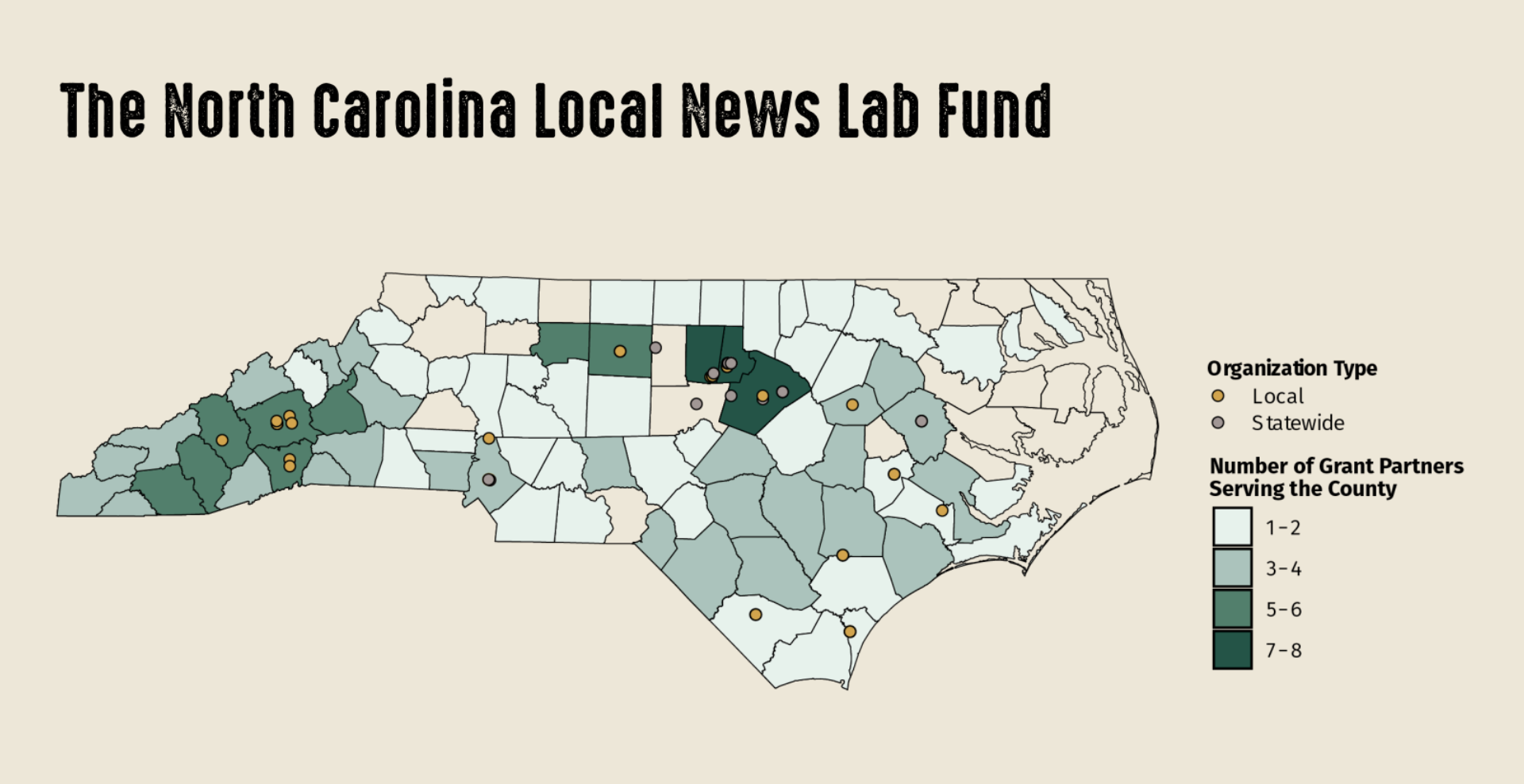

Seeing the Index for the first time prompted Hazeltine to make her own map of North Carolina. “I wanted to see how I could use the Index for a comparative analysis to inform and ground where the fund was heavily investing and where we weren’t.” With some help from friends of the fund, Hazeltine charted the concentration of grant partners across the state and then compared her map against the Civic Information Index to find new opportunities for investing in communities, make data-driven decisions, and challenge pre-conceived ideas about where those lie.

“It’s easy, when you live in one part of the state, to know it well and have passing assumptions about what the rest of the state is in different specific ways,” Hazeltine said. But those assumptions are not always reflective of the assets that communities bring to the table – especially for communities that are often painted as poor, lower-income, or rural.

Northeast North Carolina, which has been identified as a news desert, is one such example. “It’s been incredibly valuable to look [at the Index] and say, well one of the barriers to access here is clearly broadband. One of the clear needs is access to health care based on the cost burden and medical debt. But also then to say, look at the level of volunteerism in this community. Look at the level of library usage. Look at some of these different behavioral cues that help us understand beyond demographics and beyond the impacts of race-, place-, and class-based discrimination. What does that actually mean in practice, and how might the Fund intervene?” Hazeltine said.

Staying grounded during economic hardship

In the last year and half, the fund has grown to a team of three full-time staff. But it’s also been a time of new economic challenges for the state. In July, congress cut $1.1 billion dollars to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), which means that member stations across the state will no longer receive any federal funding.

“We see extreme pressure on our grant partners, we’re seeing real safety and security risks, and we’re seeing economic stressors,” said Hazeltine. All of this has rounded up to the fund making a decision to pull down the cost and time that they expect people to spend on applications, reporting, and other processes for the fund. At the same time, and especially during a period of uncertainty, Hazeltine’s team still needs information internally. What would it mean, for example, for a county with one public broadcast organization to lose 70% of its funding from the CBP? And what are the outcomes in that county currently? In this context, Hazeltine says, the Index has become a source of shared understanding to help them answer questions about the effects of national policy coming home to North Carolina.

A community-driven approach to news and information

"All of these pieces have to work together in order for an ecosystem to be efficacious for its least powerful people—and everybody else.”

As federal policy changes bring local consequences, people’s news and information needs also change and shift. Hazeltine says it became clear early in the Fund’s grantmaking that organizations who are closest to their audiences and who are incentivized to meet those needs are the ones who are best able to adapt to these changes and fill gaps as they emerge.

For example, after Hurricane Florence hit the state in 2018, the fund made a group of hurricane grants that included community-based organizations for the first time explicitly and on purpose. These included farmworker organizations, movement organizations, health clinics and organizations that worked with or deployed community health workers. “What I was seeing,” Hazeltine said, is that “many of those organizations were acting as a kind of last-mile connection deeper into communities. They were expanding distribution. They were making things accessible and in different languages. They were translating, literally and figuratively, reporting from other organizations into information that fit distribution mechanisms, whether it was just word of mouth or canvassing.”

What strikes Hazeltine about the Index, which charts outcomes related to news and information alongside outcomes related to health, equity, and civic participation, is how much it aligns with the fund’s community-centered theory of change. “Yes we believe that reporters, journalism, and journalists are essential. We can’t do without them. And given the economic situation inside journalism and news as an industry, and especially local news as an industry, to expect that smaller number of journalists—and frankly economically distressed organizations—to pull the entire weight of a community’s news and information needs is unbelievably unfair,” Hazeltine said. “All of these pieces have to work together in order for an ecosystem to be efficacious for its least powerful people—and everybody else.”

We are deeply grateful to the North Carolina Local News Lab Fund for generously sharing their story.